All made possible thanks largely due to the country’s Green Party.

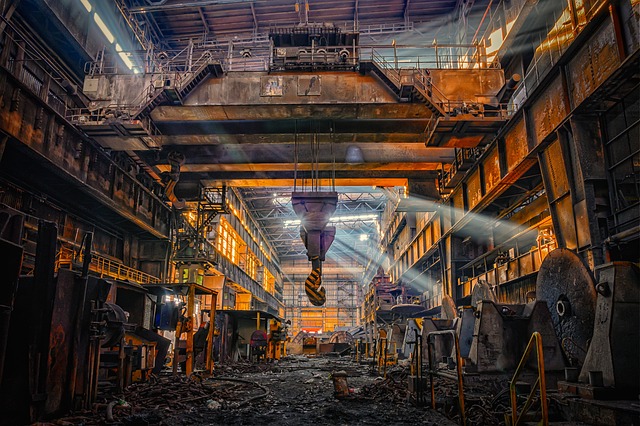

In a cavernous production hall in Düsseldorf last fall, the somber tones of a horn player accompanied the final act of a century-old factory.

Amid the flickering of flares and torches, many of the 1,600 people losing their jobs stood stone-faced as the glowing metal of the plant’s last product — a steel pipe — was smoothed to a perfect cylinder on a rolling mill. The ceremony ended a 124-year run that began in the heyday of German industrialization and weathered two world wars, but couldn’t survive the aftermath of the energy crisis.

“There’s not a lot of hope, if I’m honest,” said Stefan Klebert, chief executive officer of GEA Group AG — a supplier of manufacturing machinery that traces its roots to the late 1800s. “I am really uncertain that we can halt this trend. Many things would have to change very quickly.”

The underpinnings of Germany’s industrial machine have fallen like dominoes. The US is drifting away from Europe and is seeking to compete with its transatlantic allies for climate investment. China is becoming a bigger rival and is no longer an insatiable buyer of German goods. The final blow for some heavy manufacturers was the end of huge volumes of cheap Russian natural gas.

This chart gives a clearer picture about Germany’s situation.

This is entirely Germany’s fault. All of the warning signs were there but were ignored or goal posts were moved to achieve the elite’s vision.

The loss of cheap Russian natural gas needed to power factories damaged the German business model. Russia cut off most of its natural gas to the European Union, spurring an energy crisis in the 27-nation bloc that had sourced 40 percent of its gas from Russia. The German government conceded that it made a mistake to rely on Russia to supply natural gas through the Nord Stream pipelines under the Baltic Sea that were shut off and damaged amid the war with Ukraine.

Another bad decision was made in 2011 when Germany decided to shut down its nuclear power plants – plants that emit no greenhouse gas emissions. It was part of an overall energy strategy known as “Energiewende,” or “energy turnaround” that sought to replace nuclear and hydrocarbon-based energy with intermittent wind and solar energy—similar to President Biden’s “energy transition.” That decision has been questioned amid increasing electricity prices and possible energy shortages.

At one point, Germany was hoping clean hydrogen would be able to replace natural gas, provide energy when renewable generation came to a halt, and the Reichstag was ready to provide massive amounts of subsidies to do it. But, as Euractiv points out, such hopes were nothing more than pure fantasy.

Germany’s tech sector has vanished, a lot of its businesses are saddled with needless regulation, and it doesn’t have much of an industrial base left. If the country’s industry withers away, the Germans have nothing to fall back on. Germany’s collapse is a stark example of what happens when environmentalist utopians take the reigns of power. Worst of all, the country’s Prime Minister is all too willing to let this all happen.

PHOTO CREDIT: Pixabay